Teaching Claude to Design Better: Improving Anthropic's Frontend Design Skill

By Justin Wetch

ANTHROPIC DEFAULT FRONTEND SKILL

After building a GUI for Anthropic's Bloom framework last month (and more recently, proposing ten new behaviors it could test for), I found myself wanting to dig deeper into their ecosystem. The Bloom project gave me a lot of respect for how Anthropic approaches tooling and evaluation, and I was curious what else they had open-sourced.

That's when I discovered their Skills repository.

What are Skills?

Skills are essentially specialized system prompts that give Claude domain-specific capabilities. There's a skill for creating Word documents, one for spreadsheets, one for PDFs, and one that caught my attention: the frontend design skill. This skill is meant to help Claude generate distinctive, production-grade web interfaces that avoid generic "AI slop" aesthetics.

I started reading through it, and almost immediately something jumped out at me.

The Problem With "Don't Converge Across Generations"

The original skill file contained this instruction: "NEVER converge on common choices (Space Grotesk, for example) across generations." A few lines earlier, it said "No design should be the same."

The intention is clear. The author wanted Claude to avoid falling into repetitive patterns, to not keep reaching for the same safe fonts and layouts every time someone asks for a website. That's a real problem worth solving.

But there's an issue: Claude can't see its other generations. Each conversation is completely isolated. Claude has no memory of what it produced for the last user, or the user before that. Telling it not to "converge across generations" or that "no design should be the same" is like telling someone not to repeat what they said in their sleep. They have no access to that information.

This kind of thing fascinates me because it reveals a gap between how we intuitively think about AI and how these systems actually work. We anthropomorphize naturally, imagining Claude as a single persistent entity with accumulated habits. But from Claude's perspective, every conversation is the first conversation.

Model Theory of Mind

I've written before about what I call metacognitive scaffolding, the idea that you can dramatically improve model outputs by giving them structured frameworks for thinking through problems. But there's a prerequisite to writing good scaffolding: you have to understand what the model can actually know.

This is model theory of mind. It's the practice of reasoning about the model's epistemic state, what information it has access to, what it can perceive, what it can remember, and how it processes instructions. Without this, you end up writing prompts that sound good to humans but are confusing or non-actionable for the model.

The "don't converge" instruction is a perfect example. It's well-intentioned but impossible to follow. A better formulation might be: "Never settle on the first common choice that comes to mind. If a font, color, or layout feels like an obvious solution, deliberately explore alternatives."

Same goal, but now it's something Claude can actually do within a single generation.

Starting From First Principles

Once I noticed this issue, I got curious about what else might be improved. I decided to start by airing out my own thinking, writing an 1800-word document capturing everything I believed about frontend design: what makes interfaces distinctive, how to think about typography and color and motion, what separates memorable work from forgettable work. This became my reference point, a way to ensure I was building from a coherent foundation rather than just reacting to the original skill.

Then I went through the existing skill line by line, asking: Is this clear? Is this actionable? Does Claude have the information it needs to follow this instruction? Is it logically coherent with the rest of the document? Does it match the voice and intentionality of the surrounding text?

I think there’s quite a bit more leverage to improve this skill overall, but I wanted to do a version with targeted changes because I think it has a much better chance of actually getting merged than if I rewrote from scratch.

The Edits

The changes fell into a few categories.

Clarity and coherence. Beyond the "converging across generations" issue, there were other places where the language was murky or the skill contradicted itself. One section said "pick an extreme" when choosing an aesthetic direction, but later the skill cautioned that "the key is intentionality, not intensity." Those instructions fight each other. I changed the first to "commit to a distinct direction," which preserves the intent without the contradiction. Similarly, "design one that is true to the aesthetic direction" became "the final design should feel singular, with every detail working in service of one cohesive direction." More specific, more actionable.

Imperative voice. The original skill mixed instructional tones. Some parts were punchy and direct ("Unexpected layouts. Asymmetry. Overlap.") while others were murky and vague, not quite clear what they were asking Claude to do. I worked to make the voice consistent: clear commands that tell Claude what to do, not just what to consider.

Expanding the latent space. The skill listed aesthetic directions like "brutally minimal" and "maximalist chaos," but it was missing entire territories. Dark and moody aesthetics. Handcrafted and artisanal feels. Lo-fi zine energy. I expanded the list not to be exhaustive but to give Claude permission to explore in more directions.

The NEVER/INSTEAD structure. The original had a paragraph about what not to do (generic fonts, clichéd color schemes, predictable layouts) but didn't pair it with positive alternatives. I added an INSTEAD block: "distinctive fonts. Bold, committed palettes. Layouts that surprise. Bespoke details. Every choice rooted in rich context." Now Claude knows both what to avoid and what to reach for.

Typography overhaul. This section needed the most work. The original used adjectives like "beautiful, unique, and interesting," which sound nice as prose but don't actually tell the model what to do. Beautiful according to whom? Unique compared to what? These are aesthetic judgments, not actionable instructions. The new version focuses on concrete guidance: default fonts signal default thinking, typography carries the design's singular voice, display type should be expressive while body text should be legible, and work the full typographic range (size, weight, case, spacing) to establish hierarchy.

Color with conviction. The original guidance on color was vague, telling Claude to "commit to a cohesive aesthetic" without explaining what that meant. I rewrote it to give Claude actual directions to consider: bold and saturated, moody and restrained, or high-contrast and minimal. Lead with a dominant color, punctuate with sharp accents. This isn't just about confidence, it's about expanding the possibility space so Claude knows what options exist.

From Vibes to Data

I tested the revised skill manually for a while, running the same prompts against both versions and comparing outputs. The results felt better to me, but "feels better" isn't a contribution you can submit to a repository. If I wanted to actually open a PR, I needed data.

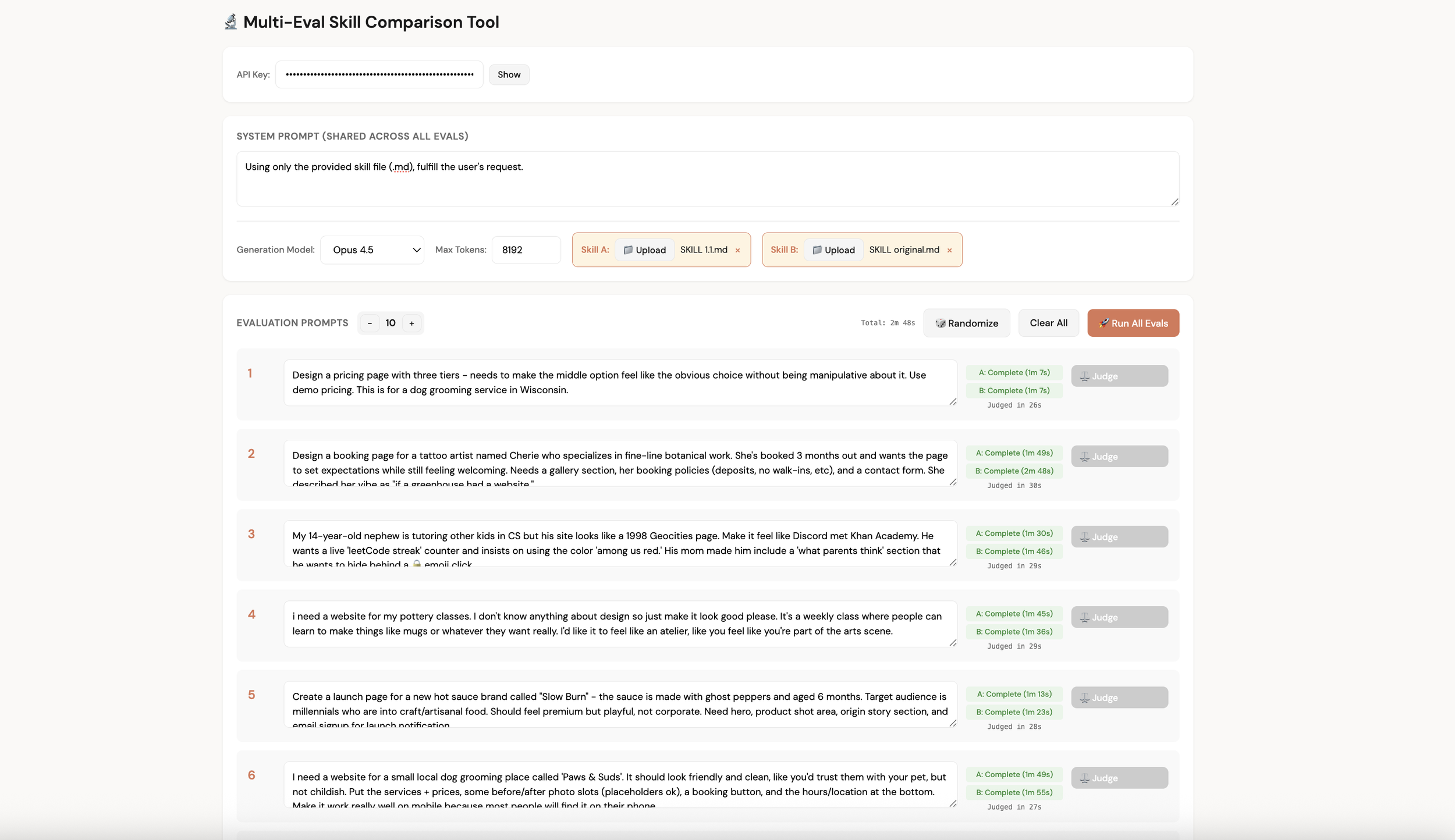

So I built an evaluation system.

The setup: a bank of 50 representative prompts covering different design contexts (landing pages, dashboards, portfolios, menus, signup flows, band pages, and so on). For each evaluation run, prompts are randomly selected and executed twice via the API, once with the original skill and once with the revised skill. A Puppeteer server captures full-page screenshots of both outputs.

Then comes the judging. The user's prompt and both screenshots (anonymized as A and B) are sent to Claude Opus 4.5, which scores each on five criteria: Prompt Adherence, Aesthetic Fit, Visual Polish & Coherence, UX & Usability, and Creative Distinction. The judge doesn't know which skill produced which output.

I ran separate evaluation suites across the Claude 4.5 model family.

Results

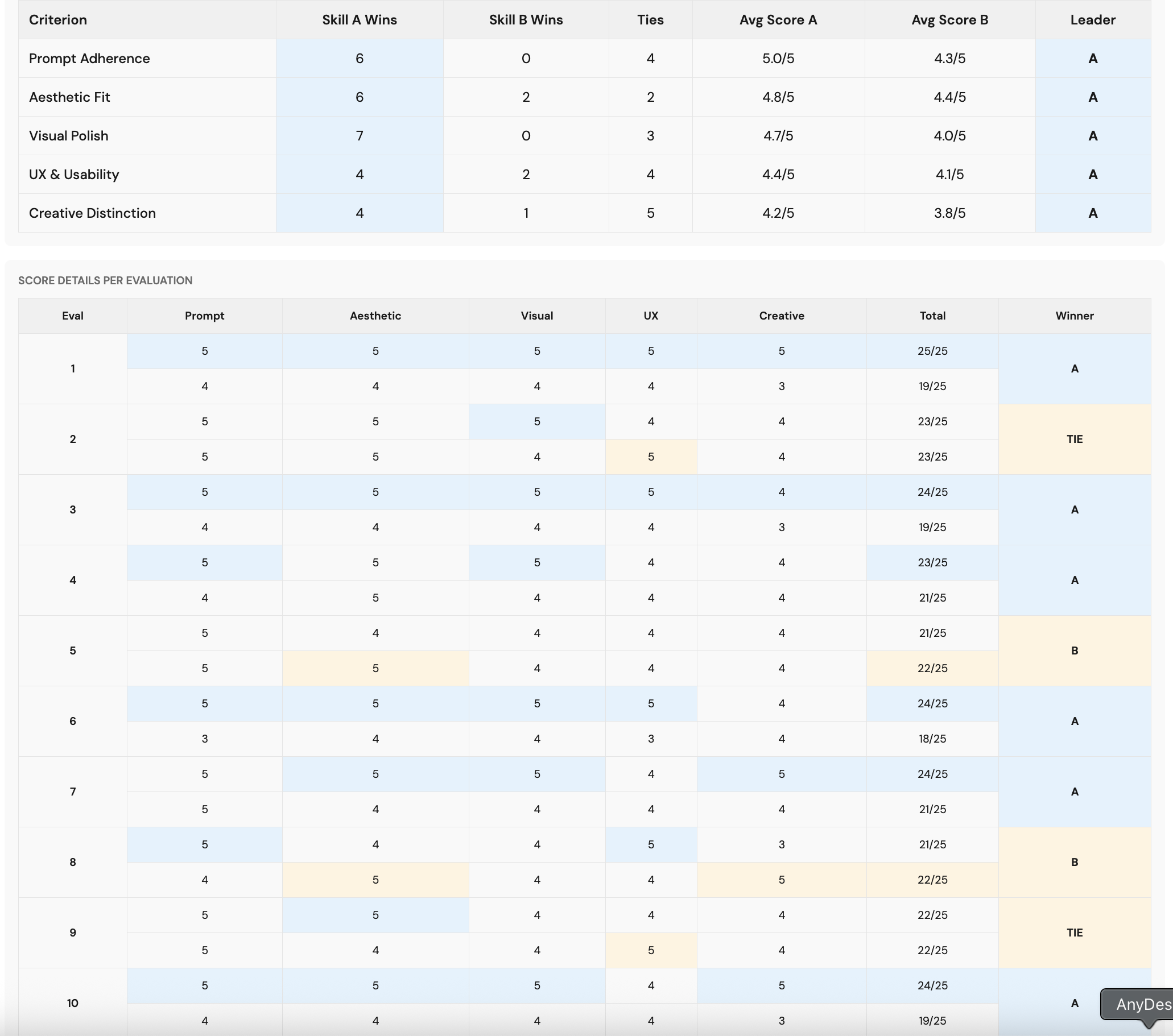

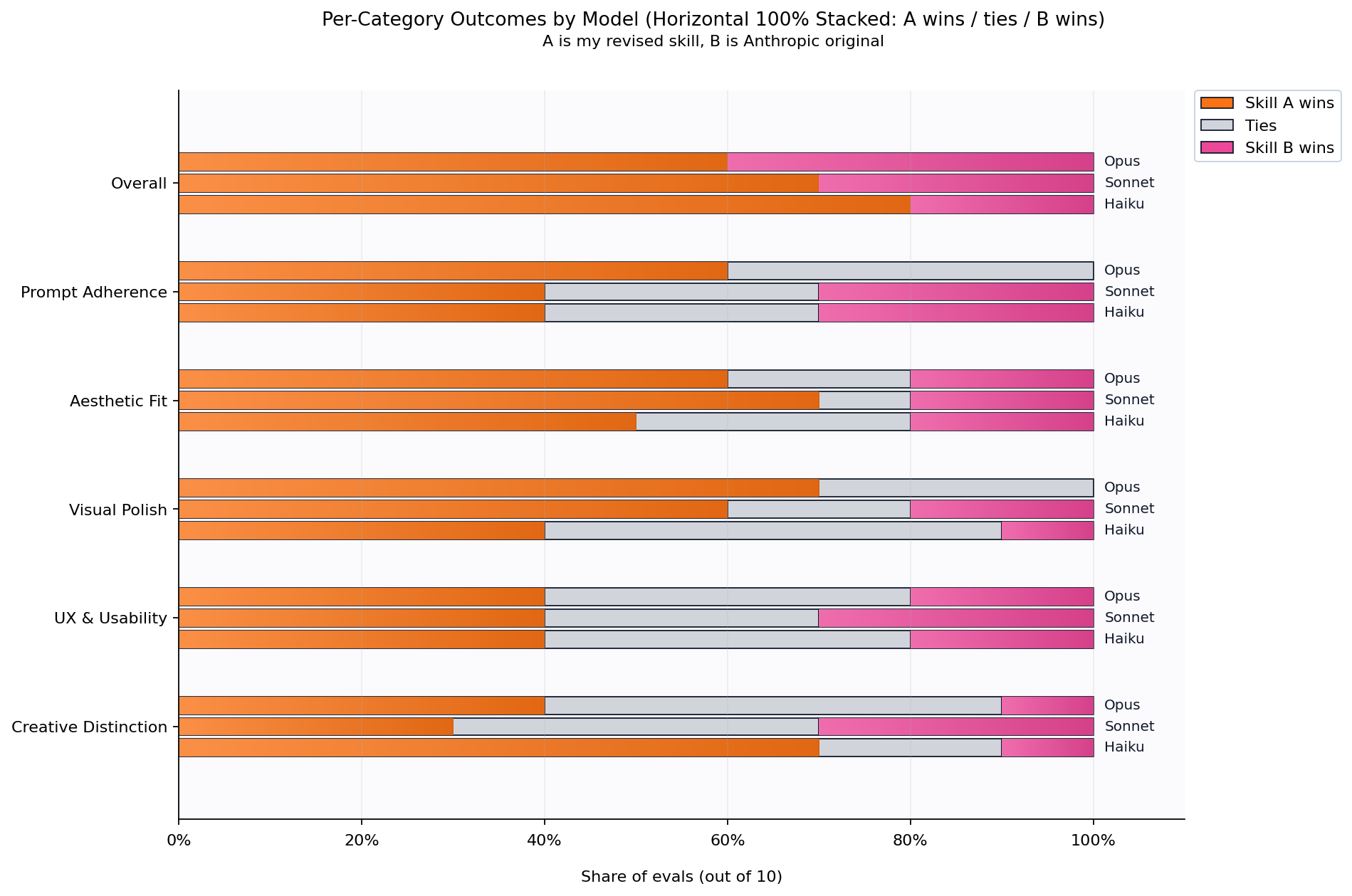

Haiku 4.5: The revised skill won 8 of 10 evaluations. The strongest gains were in Creative Distinction (7 wins, 2 ties, 1 loss) and Visual Polish (4 wins, 5 ties, 1 loss).

Sonnet 4.5: Won 7 of 10. Aesthetic Fit showed the clearest improvement (7 wins, 1 tie, 2 losses), with Visual Polish close behind (6 wins, 2 ties, 2 losses).

Opus 4.5: Won 6 of 10. Strong performance on Prompt Adherence (6 wins, 4 ties, 0 losses) and Visual Polish (7 wins, 3 ties, 0 losses).

Across all three model tiers, the revised skill won 21 of 28 decisive comparisons (excluding ties), a 75% win rate. An exact binomial test confirms this is statistically significant (p = 0.0063 one-sided, p = 0.0125 two-sided), meaning we can be confident the improvement isn't just noise.

Total of 30 evals across Opus, Sonnet, and Haiku

An Interesting Pattern

Something I didn't expect: the revised skill helped smaller models more than larger ones. Haiku showed the biggest improvement, Sonnet was in the middle, and Opus benefited least.

My hypothesis is that this reflects a ceiling effect. Opus is already quite good at frontend design, even with less specific instructions. It has more capacity to fill in gaps, infer intent, and make reasonable choices when the prompt is ambiguous. Haiku, with less raw capability, benefits more from explicit guidance. The clearer and more actionable the instructions, the more it helps models that can't compensate on their own.

If this is right, it has interesting implications for prompt engineering generally. The more capable the model, the less your prompt matters, at least for tasks within its competence. But for smaller, faster, cheaper models, careful prompting can close a meaningful portion of the capability gap.

Closing Thoughts

I submitted the revised skill as a PR to Anthropic's repository. Whether or not it gets merged, the process itself was valuable.

There's something deeply satisfying about this kind of work: taking a system prompt apart, understanding its intentions, identifying where it fails to communicate clearly, and rebuilding it with more precision. It requires a particular kind of empathy, not for users but for models. You have to hold in your head what Claude can and cannot know, what instructions it can and cannot follow, how it interprets language versus how humans interpret the same words.

I genuinely love these problems. The intersection of clear communication, design thinking, and model cognition is exactly where I want to spend my time. If you're working on similar challenges, I'd love to hear about them.

Thanks to Anthropic for open-sourcing their Skills repository and for the thoughtful work they're doing on making Claude more capable. It's a privilege to contribute, even in small ways.

For more on the Bloom GUI project mentioned above, see: Building a GUI for Anthropic's Bloom

For ten new behaviors I'd add to Bloom, see: Ten Behaviors I'd Add to Anthropic's Bloom

For more on metacognitive scaffolding and model cognition, see: Metacognitive Scaffolding