Latest software work: Building a GUI For Anthropic’s Bloom

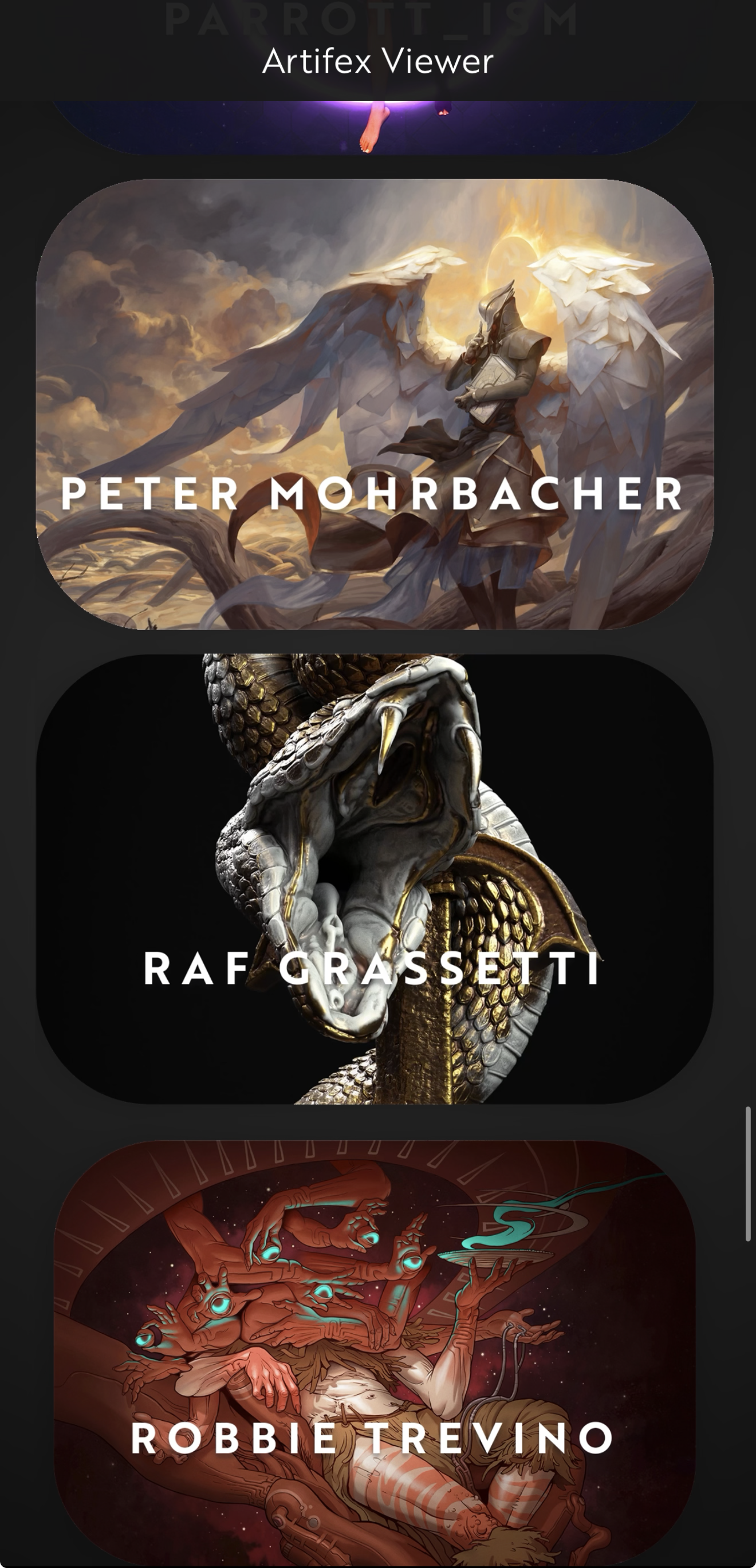

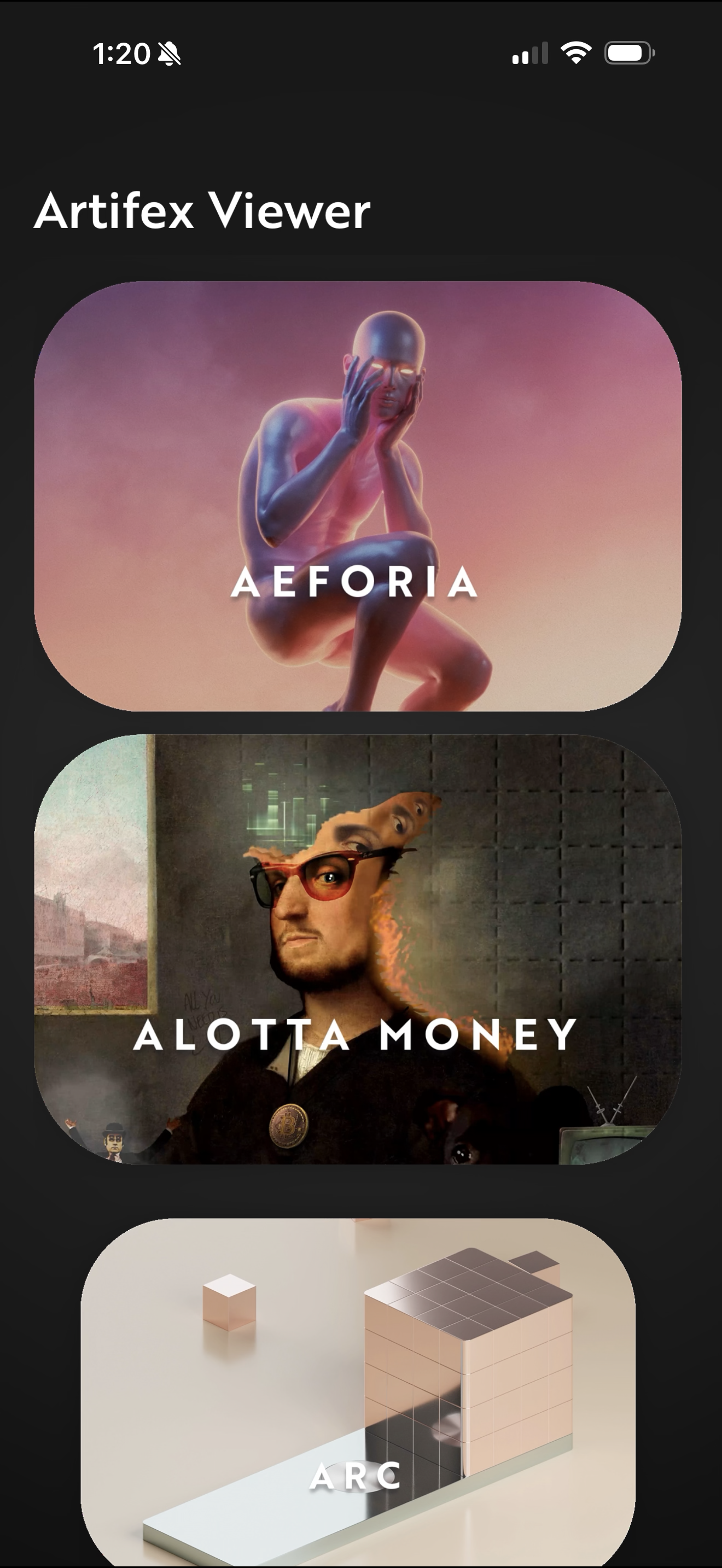

Artifex Viewer was designed, developed, and product managed by me. It is available on the Apple App Store for iOS.

Read more about the development and design process below.

Building Artifex Viewer: Dissolving the boundary between user and content

In July 2023, I saw a problem worth solving. Artifex had a collection of 40+ digital sculptures from renowned artists, but the friction between users and content was absurd. The sculptures existed as GLB files scattered across the web. To view one, you needed to know what a GLB file was, find software that could open it, and navigate a 3D viewport. This immediately eliminated 90% of potential audiences.

I wanted viewing a 3D sculpture to feel like viewing a photo. Tap, and you're there.

Constraints as architecture

The first decision was what not to build. Scope creep pressure was immediate: integrations with OpenSea, social features, marketplace functionality. Each suggestion would have ballooned the technical requirements and delayed shipping indefinitely. I pushed back. The app would do one thing well.

The USDZ format was the obvious foundation. Native iOS support meant hardware-accelerated loading with no streaming dependencies. We could bundle all 40+ sculptures locally, making every interaction instantaneous. No loading spinners, no network failures, no buffering. The entire collection lives on the device, ready the moment you tap.

This constraint shaped everything downstream. A scrolling gallery of tiles, each a high-quality 3D render. Tap a tile, enter a custom viewer. Toggle between 3D inspection and augmented reality placement. That's the entire app. No accounts, no settings screens, no feature bloat.

Spatial skeuomorphism

The visual design follows a principle I call spatial skeuomorphism, which I've written about separately here. The short version: humans are hardwired to understand the physical world, so interfaces work best when they speak the spatial dialect the brain already knows.

This is different from the visual skeuomorphism of early iOS, where apps mimicked textures like leather and felt. That was decoration. Spatial skeuomorphism mimics behaviors and physics. Elements don't just appear; they animate into frame so users understand where they came from. Scrolling has momentum and elastic edges because lists that stop abruptly feel like hitting a wall. Drop shadows and translucency establish hierarchy, telling the brain what's in front of what.

The description panel slides down from the header and back up when dismissed. The 3D/AR toggle uses matched geometry for smooth transitions between states. Spring animations with carefully tuned damping create movement that feels weighted rather than mechanical. None of this is decorative. It's functional communication through physics.

The goal is invisible mediation. Like a film score, if the interface is working, you don't notice it. You just feel it working.

Technical decisions in service of feel

Two features took disproportionate effort relative to their apparent simplicity.

The first was device-responsive rotation. Tilt your iPhone and the sculpture tilts with it, as if it exists in physical space and you're peering around it. Getting this right required capturing an initial attitude reference from the device's motion sensors and applying delta rotations with scaled sensitivity. Too responsive and it feels twitchy; too sluggish and the connection breaks. The final tuning makes the sculpture feel present, like you're holding it.

Apple added spatial photos in 2024, which does exactly this for images. A year earlier, I'd already shipped the interaction pattern for 3D objects.

The second was pivot normalization. The sculptures came from 40 different artists with arbitrary scale and pivot placement. Some were centered, some weren't. In AR, this matters: a sculpture with a misaligned pivot rotates around the wrong axis and hovers above or sinks into the detected surface. I wrote code to programmatically enforce bottom-center pivots across the entire collection, ensuring every sculpture sits naturally on whatever surface the user places it on.

These details are invisible, you would only notice if it didn’t work.

Building with GPT-4 before vibe coding existed

This was July 2023. GPT-4 had launched a few months earlier. The 8K context window version had just become available via API, and that felt luxurious at the time (laughable now, with million-token contexts). The term "vibe coding" wouldn't exist for another 18 months, until Andrej Karpathy coined it in early 2025.

But I was already doing it. My background was in Swift as a hobbyist, enough to understand the structure but not enough to build a production app without significant assistance. GPT-4 filled the gap. It could debug issues, explain why things weren't working, and help me navigate unfamiliar APIs like ARKit and SceneKit. I wasn't generating code blindly; I was using the model as a collaborator that accelerated my existing knowledge.

The result shipped to the App Store after a single review cycle, which apparently doesn't happen often. Eleven Swift files, roughly 2,000 lines of code, handling everything from the gallery interface to 3D rendering to AR plane detection and gesture recognition. Complete ownership of the stack: development, design, user experience, iteration based on feedback.

What I learned

Designing for 3D content taught me something that applies far beyond this project: the best interfaces are translations. You're bridging the gap between arbitrary digital logic and a biological processor with millions of years of spatial heuristics. Respect for that processor, understanding what it expects and delivering it, is what separates design that works from design that merely functions.

The app is still on the App Store. The sculptures still load instantly. The interactions still feel right. That's the outcome when you fight for constraints and design for the animal.